Bike Lanes on Hudson Street from Indianola across I-71: An Inexpensive Paint and Barrier Proposal

Last week, I was almost run off the road by a car on Hudson Street. This happened in the portion of westbound Hudson Street, just after Fourth Street, where the painted bike lane stops at the intersection, and bicyclists must merge with traffic.

It's a dangerous place to ride a bike, but it's also the quickest way for a cyclist to get to the protected bike lane on Summit Avenue. For most of Hudson, the only acknowledgement of non-car traffic is some painted sharrows — yet Hudson Street is a major east-west route, part of a planned connection between the Olentangy and Alum Creek trails. Hudson connects the Summit and 4th street bike lanes to the planned bike lanes on Indianola Avenue.

Despite this key position in Columbus' bikeway network, this stretch of Hudson is built only for cars and trucks.

This essay presents a proposal for building protected bike lanes on Hudson Street from the Indianola bike lane all the way across I-71 to the Hudson Street Shared Use Path. This proposal uses a combination of Jersey barriers and precast curbs for fast, low-cost installation of protected bike lanes, in combination with a road diet and a lot of paint.

TL;DR: Remove one travel lane from Hudson, and replace it with two 5' bike lanes protected from traffic by concrete barriers. The remaining lanes are generally configured as one lane in each direction with a center turn lane.

I think Columbus could do it for $550,000.

Skip to cost estimate Skip to FAQ section Comment on this post on Reddit

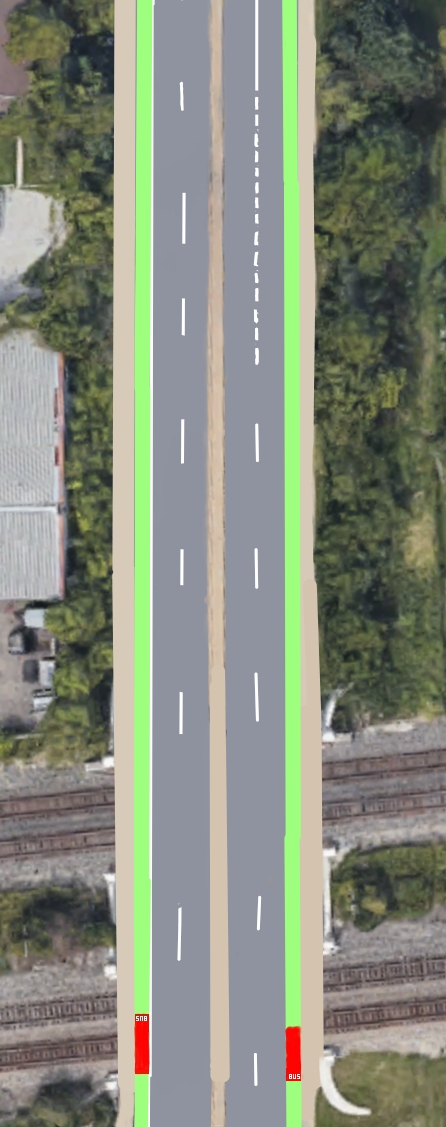

From Indianola towards I-71

We're going to scroll from the western end of this project to the eastern end. I've broken it up into separate images for easier annotation, but you can also view this as a single image.

In this map, west is up, north is right, east is down, and south is left.

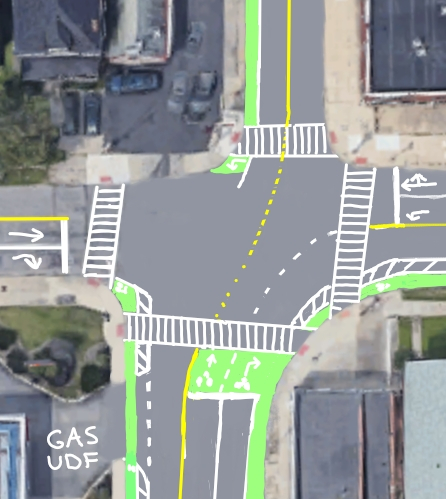

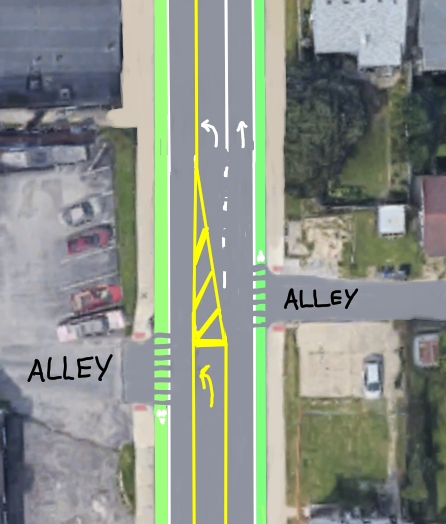

Start by painting the existing Hudson Street bike lane green, and add a turn box for westbound traffic coming south on Indianola.

This diagram uses uses conceptual designs from the early phases of the Indianola Avenue Complete Streets Study for the bike lane on Indianola: one dedicated northbound bike lane until Arcadia.

The present two eastbound lanes on Hudson are reduced to one. Additional space is reserved around the protected bike lane by using a painted buffer. The dedicated west-bound straight-ahead land and northbound turn lanes are kept.

Heading west and north, I've added a bike box on Hudson, allow bicyclists and scooters to safely position themselves ahead of cars.

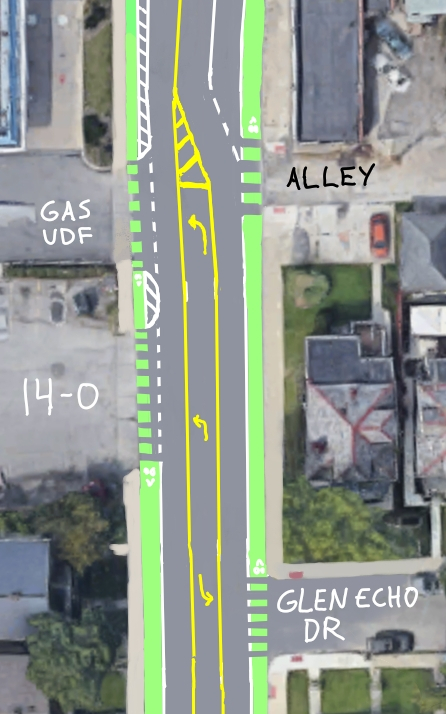

Because of the large numbers of alleys and parking lots along Hudson, I use a center turn lane to separate the east and west lanes. This provides for safe left turns onto and off of Hudson without disrupting the flow of traffic.

Where alleys and parking lot entrances cross the bikeway, the bikeway's solid green paint breaks up as an indication to bikeway users and to drivers that there's a conflict of traffic. This is an existing design pattern described in section 6.5 "Intersections and Bicycle Crossings" of the ODOT Multimodal Design Guide.

Solid barriers are provided to separate the bike lane from vehicle traffic, beginning at the 14-0 parking lot exit on the south side of Hudson, and beginning at Indianola on the north side. For more about solid barrier use, scroll down to the FAQ section.

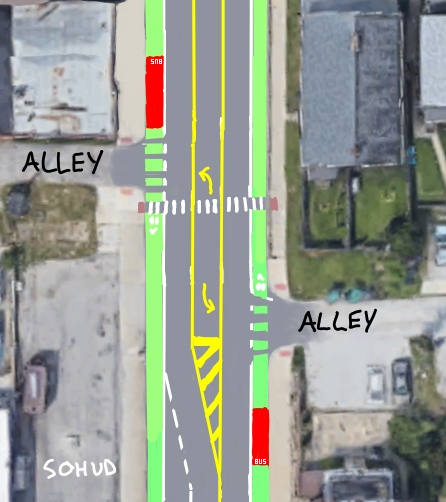

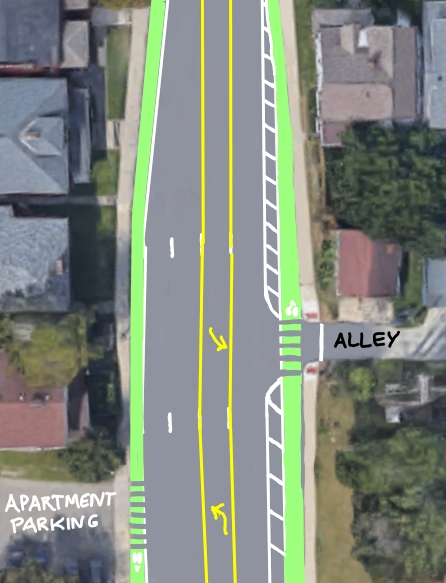

This image depicts the two bus stops closest to Summit Street, their positions unchanged from their current location. Buses stop in the travel lane to transfer passengers. The concrete protection for the bike lane also protects the bus stop users; the bike lane pavement is supplemented with a generous heaping of asphalt to raise the path to sidewalk level. This is called a floating bus stop; cyclists yield to pedestrians at the bus stop. An alternative to heaping asphalt upon the street is prefabricated plastic panels used in other US cities. Floating bus stops in this style improve transit reliability and speed by reducing the time that buses have to wait for an opening in traffic..

Also new in this diagram is a midblock crosswalk with ADA ramps positioned between the two bus stops. People already jaywalk here to change buses, so let's acknowledge the demand path with formal recognition and protection. (Unfortunately, this likely won't be installed, as the crosswalk is about 100 feet from the nearest intersection. The federal criteria for marking a new midblock crosswalk is 200 feet.)

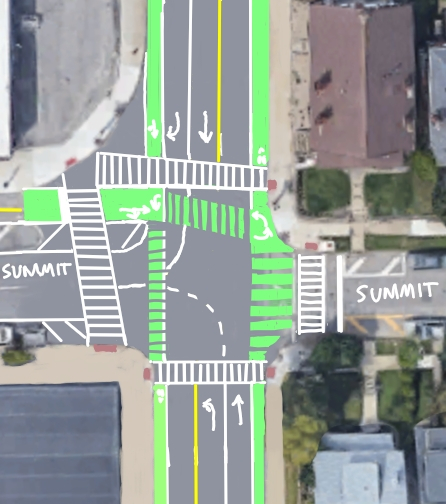

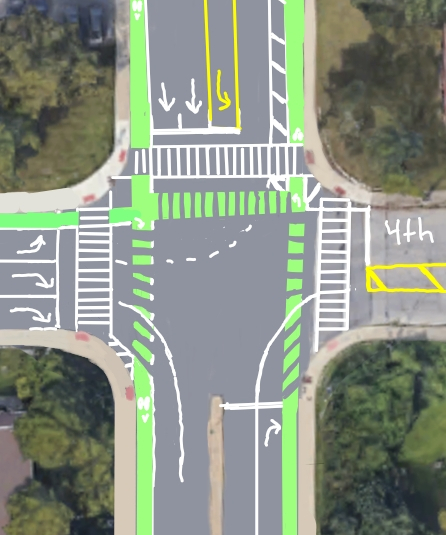

There's a lot of paint at the intersection of Hudson and Summit, I know. There's crosswalks. There's bike lanes. There's guiding dashes for vehicle traffic. There should probably be some more curbs and islands in here, but we're mostly using Jersey barriers and paint for now.

For the protection of pedestrians and bikeway users, no right turns on red are permitted at this intersection. This would ideally be accompanied by bicycle-specific signalling, like exists at the intersection of Summit and Lane. That's an added cost. In the mean time, the city could add "yield to cyclists" signs.

A large portion of the asphalt roadway here has been taken over for cyclist and pedestrian use; the design speed for right turns onto Summit is less than 10mph in order to reduce conflicts between cars and pedestrians.

Bikeway users heading south on Summit from the east will do as they currently do: stack up on Summit and wait for a favorable light to cross Hudson. This design just adds a bigger bike box.

Bikeway users heading north will take Hudson west to Indianola, rather than running against traffic on Summit to Arcadia.

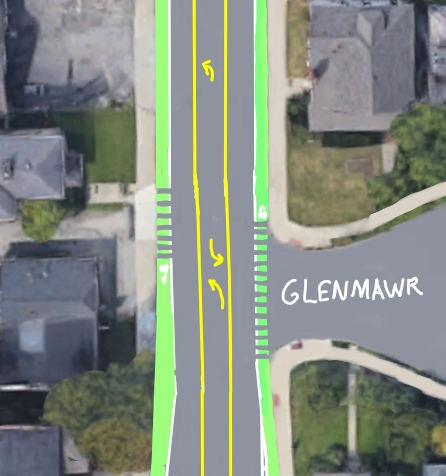

Two alleys here: one gets a center left-turn lane, and the other gets a paint barrier asking people not to please not turn into it. The alley on the south side is often used by aggressive drivers as a shortcut around the traffic light at Summit. Between the southbound traffic and cars stacking up at the light, there often simply isn't a gap in traffic for eastbound drivers to turn north into the northern alley. Therefore, this proposal removes that turn. Use Glenmawr or Arcadia to get into that alley.

I'm pretty sure I've blocked off a curb driveway into the small garage on the east side of the alley; if that's the case then oh well. Drivers can access their parking lot from the alley.

More bike lane protection gaps for another alley and for Glenmawr Avenue. The center turn lane here is again designed to get turning traffic out of the main flow of traffic. Bike lanes here are still protected with hard barriers such as Jersey barriers or precast concrete curbs, with gaps for turning traffic.

Between Glenmawr Avenue and North Fourth Street, Hudson widens. I've used this additional space to put back the second eastbound lane, so that Hudson lines up with the lanes under the rail bridges.

On the west side of the intersection, the center turn lane must stop at 4th, and so here I use it as a northbound turn lane onto northbound 4th.

On the east side of the intersection, there's a hard concrete median, which lines up with rail bridge support pillars. It can't be removed. Traffic coming west from I-71 has two lanes under the bridge; removing one of them would probably greatly anger the Columbus Fire Department. Therefore this design keeps the second lane as a rarely-used right-turn lane for northbound 4th, as is done at the intersection of East North Broadway and Indianola, just up I-71.

The current North 4th Street bike lane ends a block before Hudson, and tells bicyclists to merge with vehicle traffic. This is probably because there's no dedicated light cycle for bicyclists and pedestrians at 4th. My design anticipates a "bike scramble" or "pedestrian scramble" signal phase at the light, in which no vehicle movements are permitted, but all pedestrian and bicycle movements are allowed. This would require changing the light timings, adding beg buttons, and perhaps installing cyclist detection: A costly endeavor.

If the scramble pattern remains unapproved by ODOT, an alternative is a Leading Pedestrian Interval as described in section 8.3.4.1 "Leading Pedestrian Intervals of ODOT's Multimodal Design Guide. Under this pattern, the crosswalk lights permit pedestrians to enter the intersection before cars are allowed to enter.

Cyclist traffic headed east on Hudson from 4th will use a turn box if no changes are made to the lights.

The section of Hudson under the railroad tracks is pretty much unchanged for car traffic, with the exception of the right eastbound lane being used as a dedicated turn lane north onto 4th.

The current paint-only bike lane is protected using Jersey barriers.

The bus stops here also use the floating design. The only other change to these bus stops is that I have moved eastbound bus stop under the rail bridge, to provide shelter from the weather.

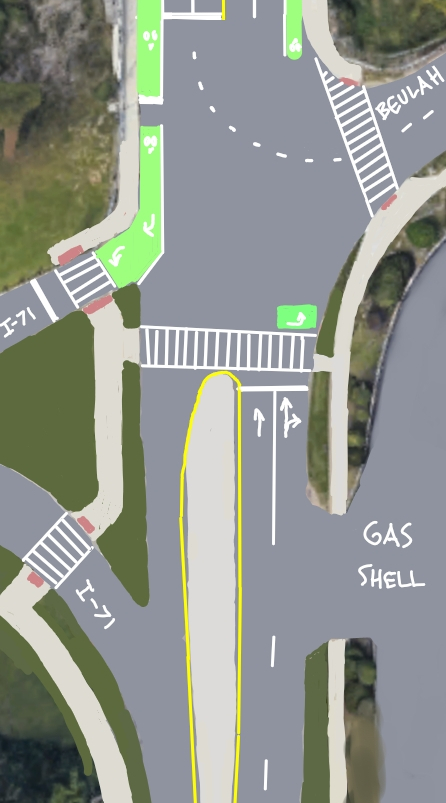

The approach to the intersection of Hudson and Silver Drive keeps much of its present design, except the protected bike lane is not crossed by the southbound turn lane. Drivers regularly cut across bicycle traffic in order to get into the turn lane, and I strongly dislike that.

This design anticipates a safety-improving "no right on red" policy at the traffic light, to protect pedestrians crossing Silver Drive, and to protect bikeway users coming south on Silver Drive who elect to use the bike box to turn left onto the I-71 bridge. Columbus has already installed "no right on red" traffic lights at the intersection of Summit and Lane.

This design also features extensive bike boxes and pavement markings to indicate safe bicyclist movements within the intersection, positioning turning cyclists waiting for a turn directly in front of turning cars, so that the turning cars will see the cyclists and not run them over by "oh I didn't see them" accident.

Here, the second left turn lane from eastbound Hudson onto Beulah Road (the approach for the I-71 north ramp) is removed. The Columbus Crew's relocation away from MAPFRE stadium has drastically reduced traffic at this intersection. The turn lane's removal gains us space on the bridge deck for a protected bike lane in each direction. I recommend full-height Jersey barriers here, rather than lower curbs, because there's a lot of truck and trailer traffic across this bridge. Lower curbs will not catch the sides of trucks which are trying to drag their trailers into the bike lane.

I anticipate bureaucratic barriers to relining the bridge. The Hudson bridge over I-71 probably is state jurisdiction or federal jurisdiction, and the lane marking tape is literally embedded in channels cut in the concrete bridge deck. Safety requires I propose it.

The eastbound bike lane terminates by directing riders onto the Hudson Shared-Use Path. Westbound traffic from the SUP uses the crosswalk and a bike box to line up for the westbound bike lane across the bridge.

Yes, it's directing bikes and scooters to ride into traffic coming up the off ramp from I-71. The reason for this is because it sure looks like the Hudson Shared Use Path designers didn't think about how people would cross I-71. There's no way for people heading east to enter the SUP at speed until they reach the commercial driveways, 300 feet beyond this intersection! Read more about this oversight in my analysis of the Hudson SUP plans.

From I-71 to Indianola

Now that you've traveled the whole route from west to east, scroll up to travel from east to west. Or view this whole map as a single image.

Note how westbound scooters and bikes don't have to merge into vehicle lanes at all, with this new route. Nor are they forced to turn onto 4th Street in order to achieve safe passage to Summit or Indianola: these road users are now given the same privileges as motor vehicles.

Cost estimate

Here's my back-of-the-envelope cost estimation math:

| Item | Cost per each | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 mile of Jersey barriers | $1000 per 8' | $333,000 |

| 0.5 mile of precast concrete curbs | $103 per 6' (source) | $45,320 |

| Paint | unknown | $100k? |

| 2 new curb ramps | $3,600 (2013) | $8,000 |

| 4 loads of asphalt to create elevated bus stops in bike lanes | $1,200/load | $4,800 |

| Revised signage | unknown | $10,000? |

| Installation costs | included | |

| Subtotal | rounded up | $500,000 |

| Consultant fees, to make the hand-drawn maps into architectural drawings | 10% | $50,000 |

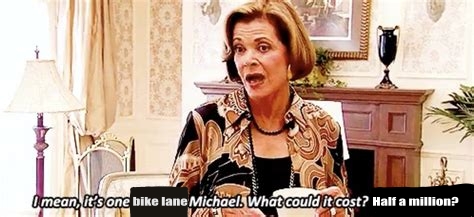

| Total | $550,000 |

Half a million dollars for two half-mile segments of protected bike lanes, not including traffic signal work. Does that seem reasonable? I don't know.

For comparison:

- Chicago spent $17 million for 100 miles of bike lane.

- Columbus spent $20 million to completely repave Hudson from I-71 to Cleveland Avenue (1.4 miles) including adding a shared-use path, rebuilding buying slivers of a bunch of houses' yards, rebuilding 4 traffic lights, and reconstructing several dozen driveways and yard stairs. And installing a new water main.

My cost estimate seems kind of high.

Frequently Asked Questions

You almost got run off the road?! Are you okay?

I'm uninjured but I'm pissed off.

What is Columbus doing for cyclist safety?

Columbus built one (1) protected bike lane on Summit Street in 2016, covering 1.4 miles. Every other bike lane in the city is unprotected, with at most a painted buffer zone separating multiton vehicles from bike and scooter riders' bodies. Columbus has spent so little effort on expanding bike lanes that the city webpage for biking describes "protected bike lanes" with a link to a webpage that describes the Summit lanes (built in 2016) in the future tense. Columbus hasn't updated their bike webpages since before 2016. Columbus hasn't built any protected bike lanes since 2016. The current year is 2022.

What about Columbus' Vision Zero plans?

To be fair to Columbus, the 2021 Vision Zero Annual Report shows that Columbus has been upgrading traffic signals and crosswalks, and they might finally complete the unprotected Indianola Avenue bike path and the Hudson Shared-Use Path by 2024.

The delays in implementing the Indianola bike lane have resulted in poor reviews of the planning process:

So three years of data collection, public meetings, consultant fees and staff time for less than three linear miles of roadway improvements. Columbus is a big, spread-out city, with 5,678 lane miles of roadway, according to the Department of Public Service. As they like to say in the venture capital world, this process is just not scalable.

Columbus' public messaging around Vision Zero principles is similarly lacking. A shining example is this tweet from Columbus' Vision Zero account: A reminder that riding bicycles on sidewalks is illegal, accompanied by a photo of a weedy sidewalk, a trash-filled gutter, and scrap metal in a painted bike gutter approaching an intersection where signage doesn't remind drivers that cyclists may be present. Columbus' Vision Zero messaging appears to be focused on changing cyclist and pedestrian behavior, rather than installing physical protections for non-drivers.

"Driver flees scene after hitting bike" is a headline that happens about once a month in Columbus, in 2022. Chicago takes visible, rapid action to address danger spots. I'm not sure what Columbus does.

It seems like you're asking a lot of Columbus.

Meanwhile, the city of Chicago announced plans on June 29, 2022, to upgrade most bike lanes in the city to have physical barriers between bikes and vehicles. Chicago will add 25 miles of protected bike lanes by the end of 2022, and finish the upgrade process in 2023. Since 2020, Chicago has added more than 125 miles of bike lanes to their network. Columbus paints a few miles a year, at most.

Columbus can do better.

Who is your design user for this project?

Referencing section 3.2.1 "User Profiles" of ODOT's Multimodal Design Guide, my design user profile is the "interested but concerned" person:

Often not comfortable with bike lanes, may bike on sidewalks even if bike lanes are provided; prefer off-street or separated bicycle facilities or quiet or traffic-calmed residential roads. May not bike at all if bicycle facilities do not meet needs for perceived comfort.

This profile represents half of the total population in Ohio. By selecting this user as the design target, this design promotes a bikeway that is accessible to everyone.

Is this just for bicyclists?

No. These bike lanes are a safety improvement for bicycles, scooters, rollerblades, wheelchairs, wagons, micromobility devices, unicycles, skateboards, strollers, dogs, children, parents, pedestrians, and anyone who isn't ensconced in a multiton steel box traveling at a high rate of speed.

Don't you worry that cars might collide with the Jersey barriers?

If a car collides with a human being, that human might die. If a car collides with a Jersey barrier, the car can be repaired, and the Jersey barrier has done its job to prevent the car from going where the car should not go. My only worry is why the car hit the barrier. I'm not worried about the car; cars are replaceable and humans are not.

Don't you worry that giving up road lanes to entitled cyclists and crazy scooter riders will make drivers mad? And mad drivers might try to collide with bikeway users?

If a driver is driven to homicidal rage at the thought of sharing the road with other people, than that person should not be a driver. Homicidal rage should not control a vehicle moving at 35mph, or indeed at any speed.

To help prevent collisions between motorized vehicles and unprotected humans, this bike lane proposal uses physical barriers between traffic modes: Jersey barriers and precast concrete curbs of the sort you see in parking lots.

Why do the bike lanes on Hudson need physical separation?

35mph, more than 6000 vehicles per day based on Indianola traffic surveys: The traffic characteristics of Hudson exceed the National Association of City Transportation Officials' guidelines for protected bicycle lanes. Hudson's street conditions also meet the criteria in the Federal Highway Administration's Bikeway Selection Guide and in ODOT's guide to install a separated bike lane or shared-use path. Hudson meets the criteria to protect its bike lane.

There's an actual legal justification for physical separation?

Section 2.5.2.2 "Bikeway Feasibility Assessment" of the ODOT Multimodal Design Guide says, "There are a variety of conditions that may indicate the need for greater separation between motorists and bicyclists, which could increase the width of the bikeway or materials used in the buffer," listing 9 criteria. Hudson meets at least 6:

- High percent of heavy vehicles (trucks and buses)

- Vehicle speeds exceed posted speed (frequent speeders in a 35)

- Presence of vulnerable populations (old folk)

- Network connectivity gaps (gap between Summit/4th and Indianola)

- Proximity to transit (many COTA and non-COTA bus routes on Hudson)

- Frequent driveways.

Why do you propose using Jersey barriers or precast concrete curbs for lane separation?

Precast concrete curbs are used by Chicago for most bike routes.

Jersey barriers provide more protection against larger vehicles, and are why I recommend them at intersections and on the I-71 bridge. The Jersey barriers' large vertical surfaces are an excellent art program opportunity; NYC DOT has operated a "Barrier Beautification" program on protected bikeways in the past.

Anything smaller than a 6" curb is going to get smashed to pieces by drivers who are oblivious, inconsiderate, or malicious. Look at the flexible plastic bollards installed on the Summit bike lane: After 6 years, many bollars are missing, and they do not stop cars from parking in the bike lane. Columbus needs better protection for road users who aren't in a multiton armored steel cage. Knee-high concrete barriers successfully stopped a car in Toronto; Columbus would benefit from that approach on parking-less Hudson Street.

Why are all your crosswalks using ladder-style crosswalk lines instead of Columbus' most-common method: two parallel lines marking the crosswalk edges?

In my experience as a pedestrian and cyclist and driver in Columbus, Columbus drivers will treat straight lines running across the road as stop bars, instead of as a crosswalk. Drivers will advance until the furthest-forward line crossing the road is somewhere under their vehicle. High-visibility crosswalks like the ladder style don't look like stop bars. Perhaps drivers won't treat them as stop bars.

Why aren't the lines in your illustrations straight? Why do you use two different colors of green for the bike lane paint?

Because I don't have access to professional transit planners' software. I did the linework by hand in paint programs. This is an amateur's impression of what a bike lane would look like.

What's with the weird raised bus stop designs?

Putting the bus stop in the bike lane, with bikes yielding to pedestrians, is a variant of the common "floating bus stop" pattern already used on Summit. For a US implementation of the specific design referred to in this plan, see the 4th Street Corridor in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Are you worried about turning traffic at alleys and driveways?

Yes. But that's also why the bike lane is protected, and heavily marked: So that turning vehicle traffic is aware of the bikeway traffic. The protected bike lane's physical barriers will require vehicle traffic to slow down to cross the bikeway, which reduces the risk of collisions for sidewalk and bikeway users.

What are potential obstacles to building this bike path?

- Car drivers may object on the grounds that this will slow down traffic in the area. They should be politely listened to and then ignored, because Hudson is unsafe. The posted speed limit is 35 and driver speeds are often as high as 45mph, depending on congestion and whether someone is trying to run a red light.

- The police department and fire department and ambulances will want to be able to bypass traffic in this corridor. Part of the reason I included a center turn lane for most of the route was to provide a safe place for emergency vehicles to pass.

- The snow plow department will say that they won't be able to plow the bike lanes. They already don't plow the bike lanes, so I don't see why this is a valid objection. The city should do do what New York did and buy a fleet of Holder C70 and Holder S100 articulated compact tractors equipped with plows and scrapers. Other options exist; check out StreetsBlog's guide to clearing snow from protected bike lanes. This would cost a few million dollars in vehicle and staffing costs, and as a bonus could be used to clear out sidewalks from the snow barriers created by Columbus' larger plows.

- Business owners in the area may object, but unlike the Indianola bike lane, this plan doesn't remove any parking. This proposal merely makes it easier for people to get around on bikes and scooters and skateboards. That should help bring customers to these businesses.

- Clintonville and SoHud residents may object to "ugly" Jersey barriers. This can be accounted for with a neighborhood art program, such as an "Adopt a Jersey barrier!" scheme. Raffle some off, sell others, and donate some to charity. Columbus might even turn a profit on this venture.

- Changes to the Hudson bridge over I-71, and to the stretch of US-23 that runs along Hudson between Indianola and 4th, may require coordination with federal agencies.

- The two-stage bicycle turn boxes depicted in this plan are allowed under FHWA interim approval, according to section 1.2.2 of the ODOT Multimodal Design Guide. However, additional regulatory approvals may be needed.

What can we do to get this built?

- If you're a normal person like me, you can share these suggestions with your contacts in city government and with city council. Talk to your local area commission. Find your neighborhood liaison and drop them a line. Fill out the 2022 Capital Investment Input Form and let the city know your spending priorities.

- If you work for city government, you can try to get this plan implemented, or a plan like it.

- If you're a city council member or if you're Mayor Ginther, you could take a page from Chicago. Read the Chicago Streets for Cycling Plan 2020 and steal all you can from it, to give Columbus a bicycle accommodation within 1/2 mile of every Columbus resident. Put it in the 2022 Capital Investments Budget. Get those revisions to the standards manuals complete and start building new bike paths.

Anything else?

Go read Brent Warren's editorial at Columbus Underground: Indianola Bike Lane Saga Shows the Need for a New Approach.

Watch this entire video:

Credits

This blog post would not have happened without:

- Google Maps and Bing Maps, whose aerial imagery contributed to these drawings. But neither is up-to-date enough to capture the new crosswalk on the north leg of the intersection of Hudson and Silver Drive.

- The Indianola Complete Streets Survey authors.

- Photos of a car colliding with a concrete barrier along a Toronto Bike Lane, which inspired me to recommend actual Jersey barriers instead of flimsy plastic bollards.

- Not Just Bikes' video Why Cars Rarely Crash Into Buildings in the Netherlands.

- The Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center cost estimates.

- Krita and The GIMP, and a shell tutorial on

for i in {1..11}; do cp combined.jpg "$i.jpg"; done. - Brent Warren's editorial.

- Editing and review passes from friends.

- That driver that almost ran me off the road.